|

© Copyright 2003 by the

Photography Criticism CyberArchive. All rights reserved. photocriticism.com |

|

This printout is for reference only.

Reproduction and distribution of multiple copies prohibited. |

Archive Authors

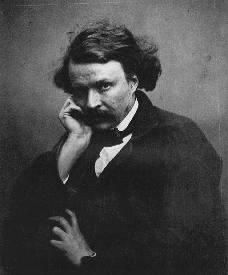

Nadar (Gaspard Felix Tournachon)

(1820-1910)

Though best known today as a photographer, Gaspard Felix Tournachon -- who took the name Nadar as a pen name early in his multifacted career -- studied medicine, then abandoned that discipline for a bohemian life as a novelist, journalist, and caricaturist (what we now would call a cartoonist) before taking up photography.

Paris-born to a father from Lyon, a printer who also published Alexander Dumas's fist novel,  Tournachon enrolled in medical school in Lyon upon his father's death in 1837. At the same time, he began working for small newspapers in that city. A year later, he returned to the city of his birth, gave up medicine, and, under the nom de plume of Nadar, commenced his contributions to assorted Parisian journals. In 1839 -- the year of photography's official invention -- he founded a lavish, short-lived magazine that lasted nine issues. He also wrote about theater and began to familiarize himself with the world of art and literature. His first novel appeared in 1846. In 1848 he became staff caricaturist for Charivari, the most influential satirical journal of its time. By the age of 30 he was publishing some two thousand drawings per year in that magazine and others.

Tournachon enrolled in medical school in Lyon upon his father's death in 1837. At the same time, he began working for small newspapers in that city. A year later, he returned to the city of his birth, gave up medicine, and, under the nom de plume of Nadar, commenced his contributions to assorted Parisian journals. In 1839 -- the year of photography's official invention -- he founded a lavish, short-lived magazine that lasted nine issues. He also wrote about theater and began to familiarize himself with the world of art and literature. His first novel appeared in 1846. In 1848 he became staff caricaturist for Charivari, the most influential satirical journal of its time. By the age of 30 he was publishing some two thousand drawings per year in that magazine and others.

To assist his brother Adrien, Nadar in 1853 offered to set him up in a photography studio, first arranging for Adrien to study the craft with the landscape photographer Gustave Le Gray. (The collodion process had just been introduced.) He had a second motive for this generous act: He was about to embark on the creation of the Panthéon-Nadar, an ambitious survey in caricatural lithographs of the thousand most important cultural figures of his time, and needed photographs to work from in many cases. The Panthéon-Nadar failed, but Nadar nonetheless established the studio for Adrien and, in 1854, made his own first photographs, studies of the mime Charles Deburau. In 1855 he published his classic portraits of the writer Charles Baudelaire, becoming immediately the most sought-after portraitist in France. Historian Helmut Gernsheim considered him "the photographer par excellence of the intelligentsia of the Second Empire and the Third Republic."

His life thenceforth reads like a novel in itself. He sues his brother for misappropriating the pseudonym Nadar (and wins in court). He makes the world's first aerial photographs, bird's-eye views of Paris from a hot-air balloon (becoming in the process an obsessive champion of lighter-than-air craft). He produces the first successful underground photographs in the catacombs and sewers of Paris. He publishes an autobiography of his youth, and opens his own grand studio at the highly fashionable address of 3, boulevard des Capucines. He publishes more books of his own writings, edits books by others, smuggles a manuscript for the exiled Victor Hugo, uses his balloon for courier and propaganda work during the Franco-Prussian War, and finds time to mount the first public exhibition of work by the Impressionists in his atelier in 1874.

After the conclusion of the Franco-Prussian War Nadar photographed less and less, but published a steady stream of books between 1871 and 1883. His last major contribution to the medium of photography was his 1886 collaboration with his son Paul of what is considered by many the first photo-interview, a series of pictures of the prominent chemist and physicist Michel Eugène Chevreul accompanied with excerpts from what this distinguished scientist was saying at the moment each picture was made. (The occasion was Chevreul's hundredth birthday.) However, in this instance it was Nadar who asked the questions and Paul who made the photographs.

Nadar's most notable contribution to the literature of photography is his autobiography, Quand j'étais photographe (When I Was a Photographer), which appeared in 1900, when he turned 80. Though, according to scholars, he occasionally plays fast and loose with the facts, the book provides a largely reliable, highly opinionated, distinctly idiosyncratic retrospective consideration of a life in photography. Written by a practiced author with a deep connection to the notable authors of his time, it offers a unique voice as well as an intriguing tale, making it perhaps the first photographer's autobiography worth considering as a work of literature in itself.

Not exactly a continuous saga, the book seems more a suite of meditations, or a selection of views -- of his experiences, of Parisian life and culture, of photography itself -- from different perspectives. Its fourteen chapters offer, variously, a social chronicle of urban life on the continent, an account of photography's early years by one who helped to shape it, and a summary of 19th-century Europe's creation of and adaptation to this astonishing new medium. We offer five complete, self-contained chapters of it here in the original French, and will fill out the French version online over time. If possible, we will add to this an English translation, should one become available to us.

-- A. D. Coleman

In the Photography Criticism CyberArchive:

Books

A Nadar Bibliography

A comprehensive Nadar bibliography can be found in the exhibition catalogue Nadar, by Maria Morris Hambourg, Françoise Heilbrun, and Philippe Neagu (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art New York and Yale University Press, 1994).

(Photo credit: Nadar, "Self-Portrait," ca. 1854-55. )